|

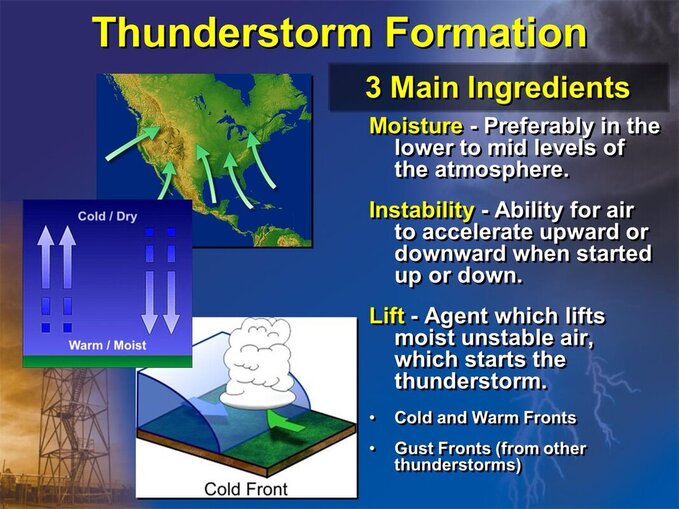

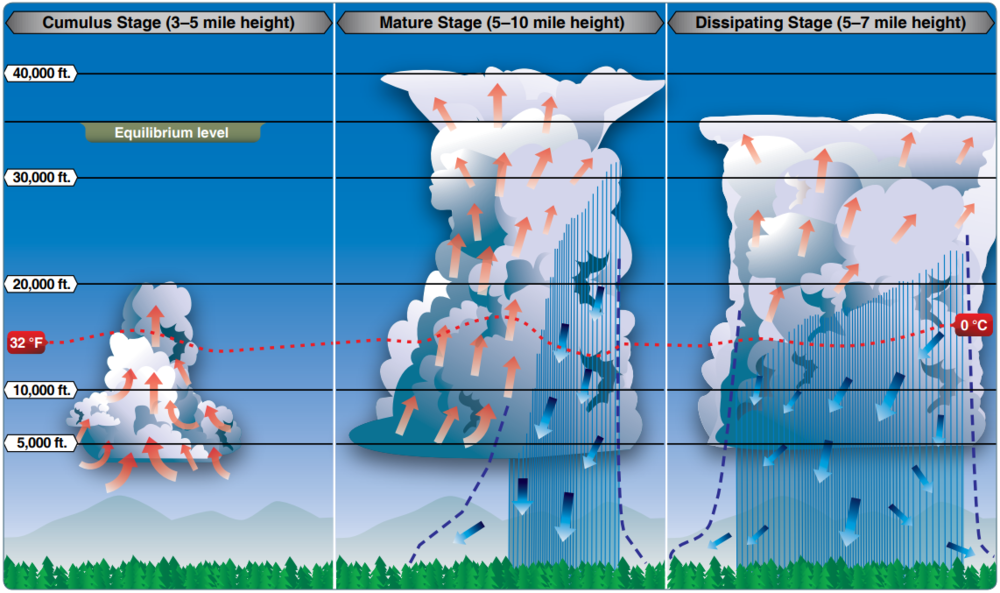

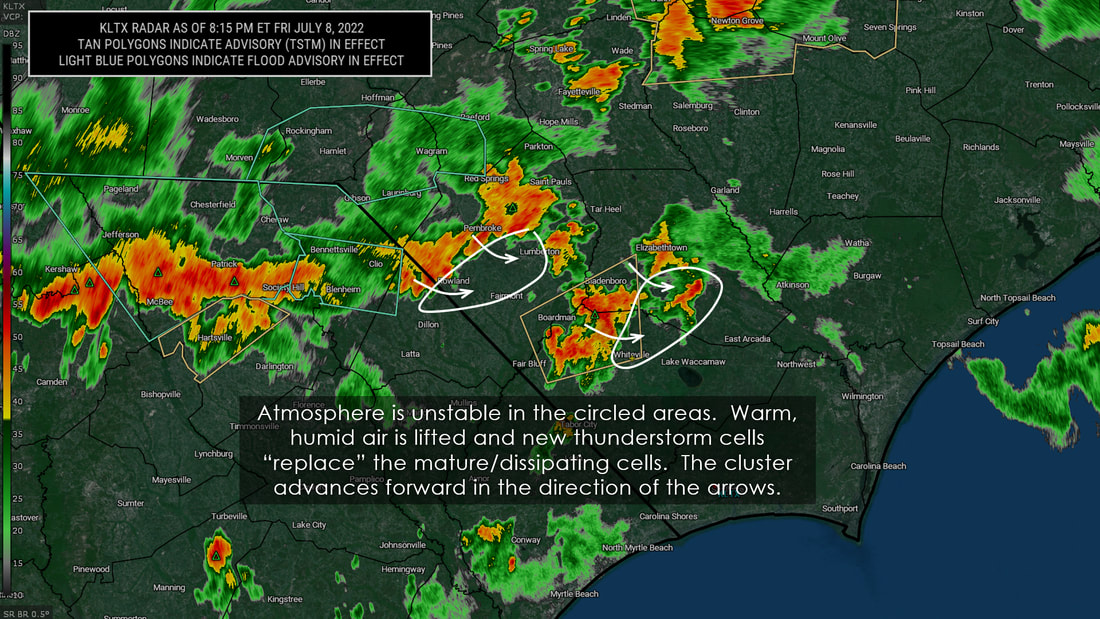

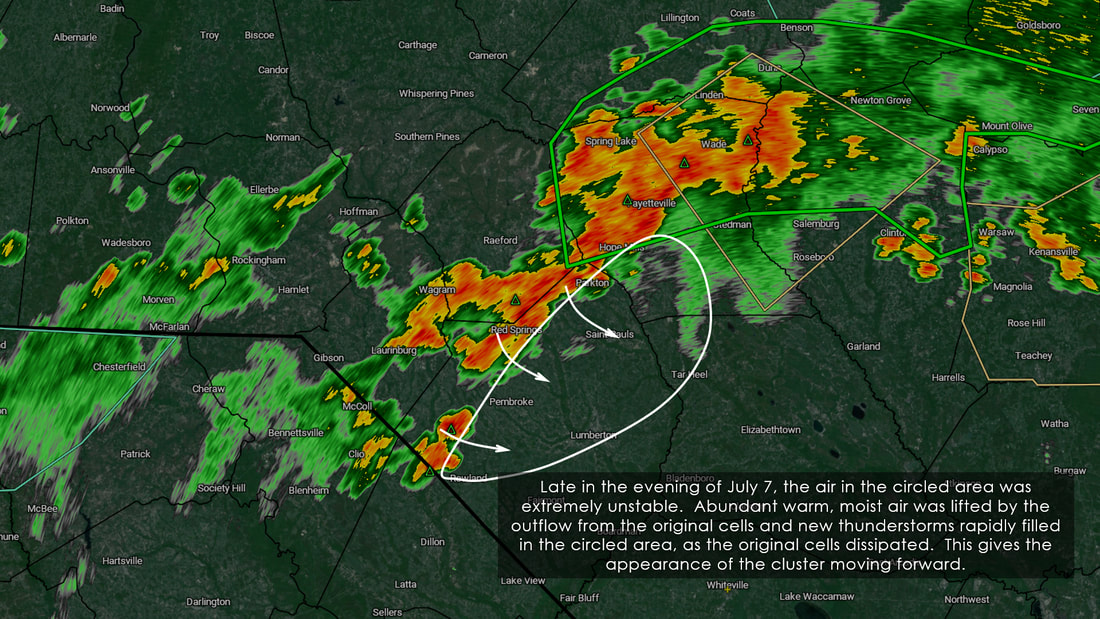

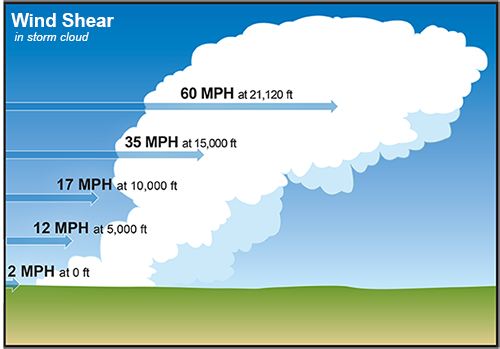

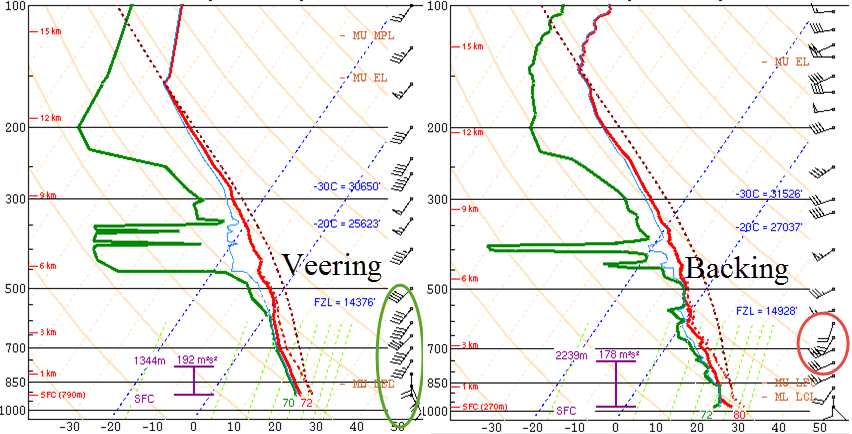

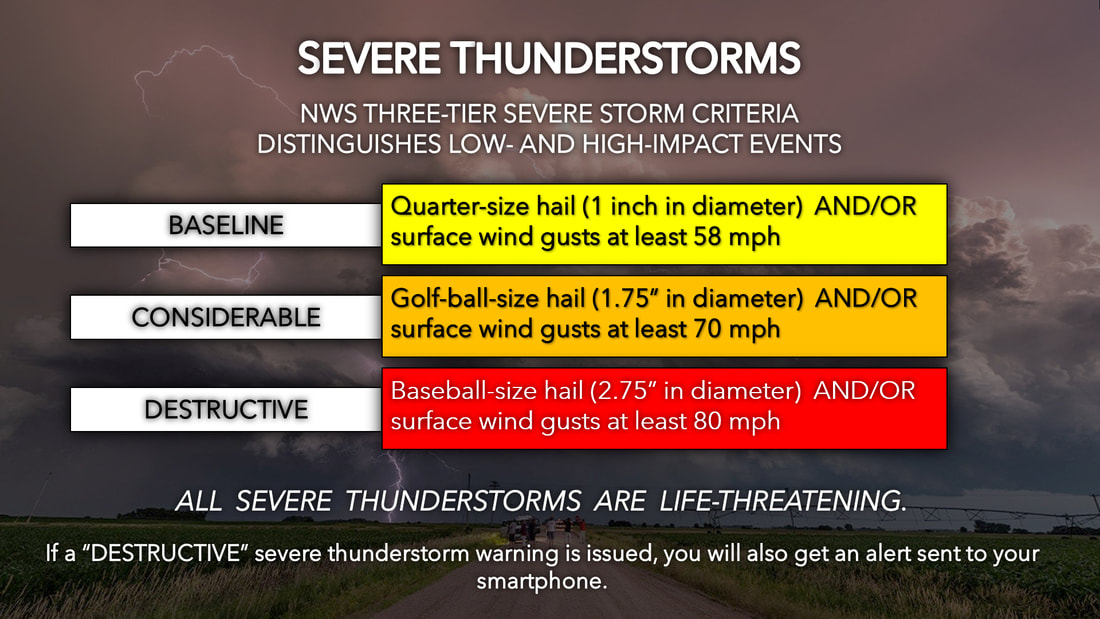

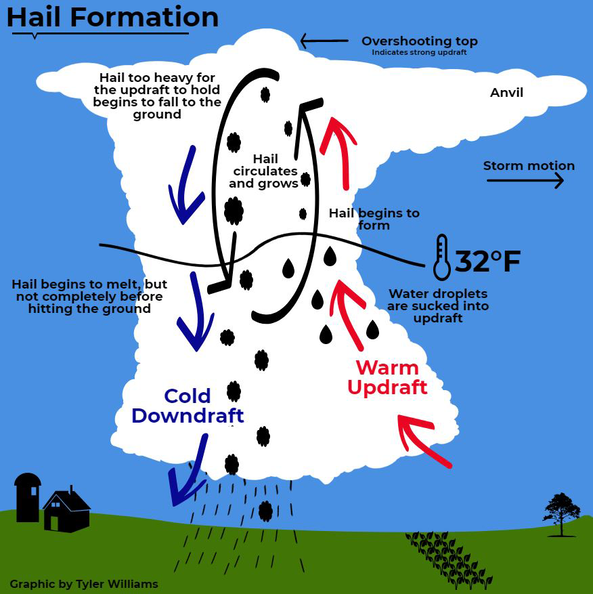

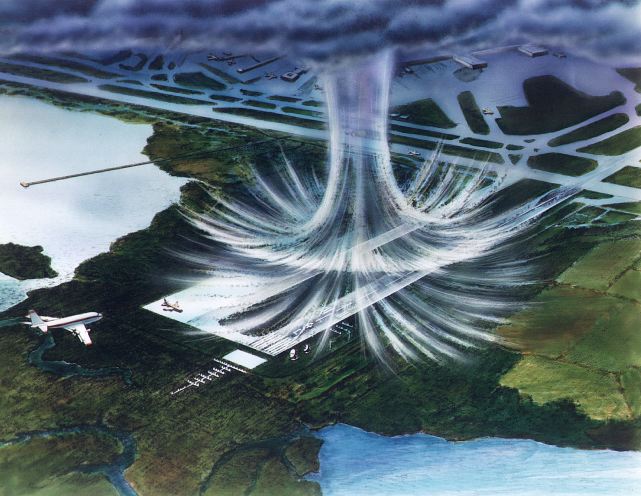

Thunderstorms... all thunderstorms... are dangerous and can be deadly. They are also quite beautiful. A thunderstorm is simply a tool our dynamic atmosphere uses to stay in balance. Like everything else on Earth, they go through a life cycle, from beginning to end, birth to death. What is a thunderstorm? Simply put, a series of updrafts and downdrafts. The American Meteorological Society defines a thunderstorm as "a local storm, invariably produced by a cumulonimbus cloud and always accompanied by lightning and thunder, usually with strong gusts of wind, heavy rain, and sometimes with hail." We've had a lot of thunderstorms over the past several days, so I thought I'd do a "Science|Saturday" post to provide a "peek behind the curtain" on what makes a thunderstorm. This is NOT to be used as a complete, detailed text on everything thunderstorms, but will provide you with a basic understanding of one of the many processes in our atmosphere. This is a long post with quite a bit of reading, but I tried to make it as "plain English" as I could. To develop a thunderstorm you must have warm, humid air at the surface, an unstable atmosphere, and a trigger to move air upwards to that unstable level. The trigger can be anything from a cold front to surface convergence to an old outflow boundary to surface heating and free convection. DEVELOPMENT STAGE: A "bubble" of air (called a 'parcel') is lifted to a level where moisture condensation begins and latent heat is released. (Latent heat is energy that is in a hidden form which changes a solid into a liquid or vapor, or a liquid into a vapor, without changing the temperature.) Once the latent heat is released, the buoyancy of the rising air is enhanced. Much of the energy for thunderstorm development comes from this release of latent heat, as this is what allows that "bubble" to remain warmer than the surrounding air over great vertical (up-and-down) depths. Once the rising "bubble" is able to pass the transition level from stable to unstable, rising air within the cloud becomes warmer than the surrounding air and it accelerates upward, which helps to bring in more air from below. These rising air currents are called UPDRAFTS. A growing cumulus cloud is observed in this stage. The early stage of thunderstorm development is dominated by updrafts. MATURE STAGE: Eventually, the processes that transform a cloud of small droplets into precipitation-sized drops take over and the cloud particles (liquid droplets and ice) get so large that the updraft can no longer hold them up and they begin to fall. As precipitation falls below the cloud base, it encounters a region of the atmosphere that is unsaturated. Thus, some of the liquid water and ice evaporates on the way down to the ground. This is called EVAPORATIVE COOLING. Falling air "bubbles," containing precipitation, can become colder than the surrounding environmental air due to this evaporative cooling. In a sense this is opposite to the unstable updraft. Falling air parcels that become colder (and more dense) than the surrounding environmental air will accelerate downward, causing more air from above to follow. This evaporatively cooled air, which accelerates downward, is called a DOWNDRAFT. Most thunderstorms produce downdrafts, and if conditions are right, they can be quite strong and destructive (such as a macroburst or microburst). Sraight-line wind damage occurs from thunderstorm downdrafts. When downdraft air hits the ground it spreads outward and moves along the ground, as a GUST FRONT. That blast of cold air hitting in the face just before the onset of a strong thunderstorm is the gust front. DISSIPATING STAGE: A thunderstorm begins to die when its energy supply of warm, humid air in the updrafts is cut off. Once that energy supply no longer exists, the storm dies. Just like your car will no longer run when there is no more fuel in the tank. Lighter rain may continue to fall for a short time as updrafts are no longer holding up the larger cloud particles. Sometimes the spreading cold air at the surface (gust fronts) can initiate new thunderstorms tens or even hundreds of miles away. ORGANIZED CLUSTERS / SEVERE STORMS: Most severe thunderstorms are parts of clusters or some other organization that allows updrafts to continue. Merging gust fronts (also known as outflow boundaries) is one such way this happens. Where these boundaries meet, there is an area of CONVERGENCE at the surface, which forces air to rise. To understand convergence, imagine a perfectly smooth swimming pool. You are standing at one end and your friend is at the other. You both drop a rock into the water at the same time. Eventually the water ripples will reach each other. The point where the water ripples reach other is convergence. If the atmosphere is unstable at this convergence, new thunderstorms are initiated quite easily. This is the mechanism that produces multi-cell clusters of storms, similar to what we've seen over the past several days. Here are a couple of radar screen grabs showing this "in the real world." Most often severe thunderstorms require VERTICAL WIND SHEAR to form. Vertical wind shear is a situation where the winds change in speed and/or direction at different altitudes. Meteorologists use a SKEW-T diagram to look at vertical wind shear. Favorable types of vertical shear interact with thunderstorms to enhance and maintain vertical draft strengths. Thunderstorm squall lines can form in areas where the vertical wind shear is such that the wind speed increases with increasing altitude. "Hang on, Chris, you're losing me here." Individual thunderstorms are moved (or steered) by the winds at roughly 18,000 feet above sea level. This number isn't absolute and can vary under different situations. If the wind speeds at this level are faster than the surface winds, a steady supply of warm and humid air moves into the storm. This causes new thunderstorms to develop as the original storm dissipates. In truth, squall lines aren't the same "original" thunderstorm; however, are new storms that generate following the same procedure that you read 231 hours ago at the top of this long post. "SO WHAT MAKES A STORM SEVERE?" The National Weather Service defines a severe thunderstorms based on hail size and surface wind gusts. That's it. That's the criteria. Lightning frequency and intensity have no bearing on whether or not a storm is severe. All thunderstorms produce lightning. Rainfall intensity has no bearing on whether or not a storm is severe. ANY thunderstorm has the capability of producing flash flooding. In August 2021, the National Weather Service came out with a three-tier system to classify severe thunderstorms. This helps to distinguish low- versus high-impact events. Hail is a form of frozen precipitation. Hailstones usually measure from 0.2 inch to greater than 6 inches in diameter. Hail forms in thunderstorms with intense updrafts, high liquid water content, great vertical height, large water droplets, and where a good portion of the cloud layer is below 32°F (0°C). Hail is composed of transparent ice or alternating layers of transparent and translucent ice. These layers are deposited on the hail stone as it travels up and down through the cloud, suspended aloft by the powerful updraft of a storm. The upward motion of the hailstone ends when its weight overcomes the updraft and it begins to fall. When looking at straight-line winds in a severe thunderstorm, we talk about microbursts. A MICROBURST is a small very intense downdraft that descends to the ground, then spreads out along the ground as a strong winds moving away from the microburst core. Microbursts can produce wind speeds of greater than 150 miles per hour and thus are capable of causing significant damage. Microburst winds can be stronger than the winds observed in some hurricanes and tornadoes. Because microbursts and tornadoes are both associated with severe thunderstorms, it is common for people to mistake microburst wind damage for tornado wind damage. Lets take a closer look at the microburst image. When that massive amount of rain and hail, along with very dense, cold air, falls from the cloud, it can't go THROUGH the ground, so it flows out in a 360° direction. These winds can and often do produce damage similar to that of a tornado. They can SOUND like a tornado when they're occurring. That is part of the reason they are often mistaken for tornadoes. National Weather Service officials do storm surveys after storms and they can discern, by looking at the damage path (especially from above), and know instantly whether or not a tornado occurred. That'll conclude this post for today, congratulations if you have made it all the way through. You are now competent on thunderstorms and have a greater understanding of how they develop and how they "work." Our next "SCIENCE | saturday" topica will be supercell thunderstorms and what sets them apart from what we looked at today.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorChris. Just... Chris. Archives

December 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed